The Summer of 1940: Britain Stands Alone Against Nazi Germany

In the summer of 1940, after France succumbed to the German forces, Britain emerged as the sole Western European nation yet to bow to Hitler’s fascist regime. Aiming to launch an assault on British soil, the German military recognized the necessity of dominating the English Channel, which lies between southern England and northern France, thus initiating Operation Sea Lion.

The plan envisioned deploying 100,000 German troops across the beaches of Kent and Sussex to commence the invasion of England. However, to achieve this, the Nazis needed to secure aerial superiority.

The Air Power Balance

Britain’s air defense heavily relied on two types of aircraft: the Spitfire and the Hurricane, while the German Luftwaffe boasted the Messerschmitt fighters and Junker bombers—among the best aircraft of World War II.

The Forces at Play

Germany prepared for this historic aerial combat with a fleet of 2,550 aircraft, against Britain’s 1,963. British aircraft were well-made but lacked experienced pilots, many of whom had perished in the conflict in France. These losses were irreplaceable.

The Strategic Failure of Hitler’s First Attempt

The Battle of Britain marked the first campaign in history where military forces engaged each other exclusively in the air. It was unprecedented in its duration and intensity of aerial bombardment and dogfighting.

The German leadership hoped initial attacks would draw a significant number of British fighters. However, after the first clashes, the RAF smartly repositioned its aircraft further inland, rendering German attacks ineffective.

Adolf Galland, a young Luftwaffe general, likened the German planes to “dogs on a leash, eager to attack but restrained by distance.”

The fact that the battle was fought over British skies meant that RAF pilots who parachuted out of downed planes could rejoin the fight shortly after, whereas downed Luftwaffe pilots were taken prisoner.

By the end of July, the RAF had lost 150 aircraft, while Germany had suffered 268 losses. In August, Germany shifted its tactics to bombing airfields, radar stations, and command centers, hoping to prevent RAF planes from taking off. Without radar, the RAF could not effectively organize its defense against German assault strategies.

The Turning Point

August 13, 1940, known as “Eagle Day,” was when Hitler ordered a full-scale assault to decimate the RAF, marking the next phase of the operation. The Luftwaffe launched two major attacks, totaling 1,485 sorties, targeting airfields, radar installations, and aircraft factories in southern England.

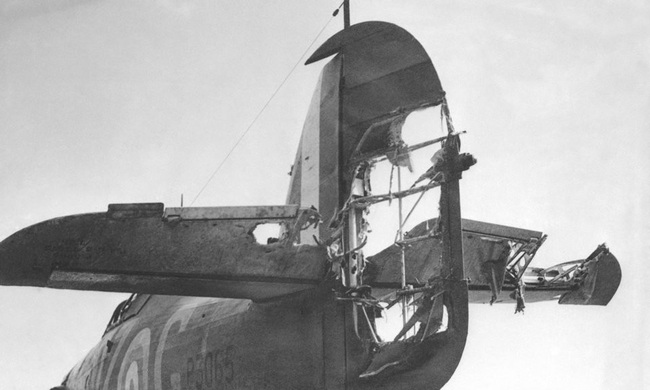

In mid-August, Germany launched a new wave of attacks. The RAF smartly engaged and then retreated from the range of German aircraft, inflicting heavy losses on the Luftwaffe. August 18 saw the fiercest day of fighting, with substantial losses on both sides: Germany lost 100 planes, while Britain lost 135.

Herman Goering’s critical mistake was his failure to decisively target British radar installations and underestimating the exhaustion faced by the RAF in prolonged aerial combat. Shifting focus to bombing cities indirectly allowed the RAF to regroup and gave pilots much-needed rest.

The decisive battle occurred on September 15, with 1,500 aircraft from both sides engaged. Prime Minister Churchill likened it to the battle of Waterloo. On that day, Churchill, smoking his cigar, watched the battle unfold from the Fighter Command’s headquarters at Uxbridge. An officer requested he extinguish his cigar due to a no-smoking policy, but that extinguished cigar would later become a talisman for RAF pilots.

September 15 marked the last day Hitler was willing to wait for a victory in the air over Britain. On that day alone, Germany lost 60 aircraft, while Britain lost 28. By September 17, Hitler is said to have indefinitely postponed the invasion of Britain, though sporadic bombing continued afterward.

By the end, Britain had lost nearly 80% of its fighter planes, roughly 1,744 aircraft. The Luftwaffe suffered nearly 75% losses, approximately 1,977 aircraft. The battle inflicted over 3,700 aircraft losses in total on both sides. Experts cite another reason for the Nazi defeat: the Luftwaffe’s disruption by the dense fog characteristic of British weather.

This was Germany’s first significant military defeat and marked a crucial turning point in World War II history. The British viewed it as a decisive victory, halting the westward advance of Nazi forces.

Moreover, this victory led to Britain’s involvement in the Battle of the Atlantic and the Normandy invasion in 1944.

The Battle of Britain is regarded as a quintessential air defense battle of the 20th century. September 15 is annually commemorated as a historic aerial combat day, a milestone in thwarting the Nazi campaign to conquer all of Europe.